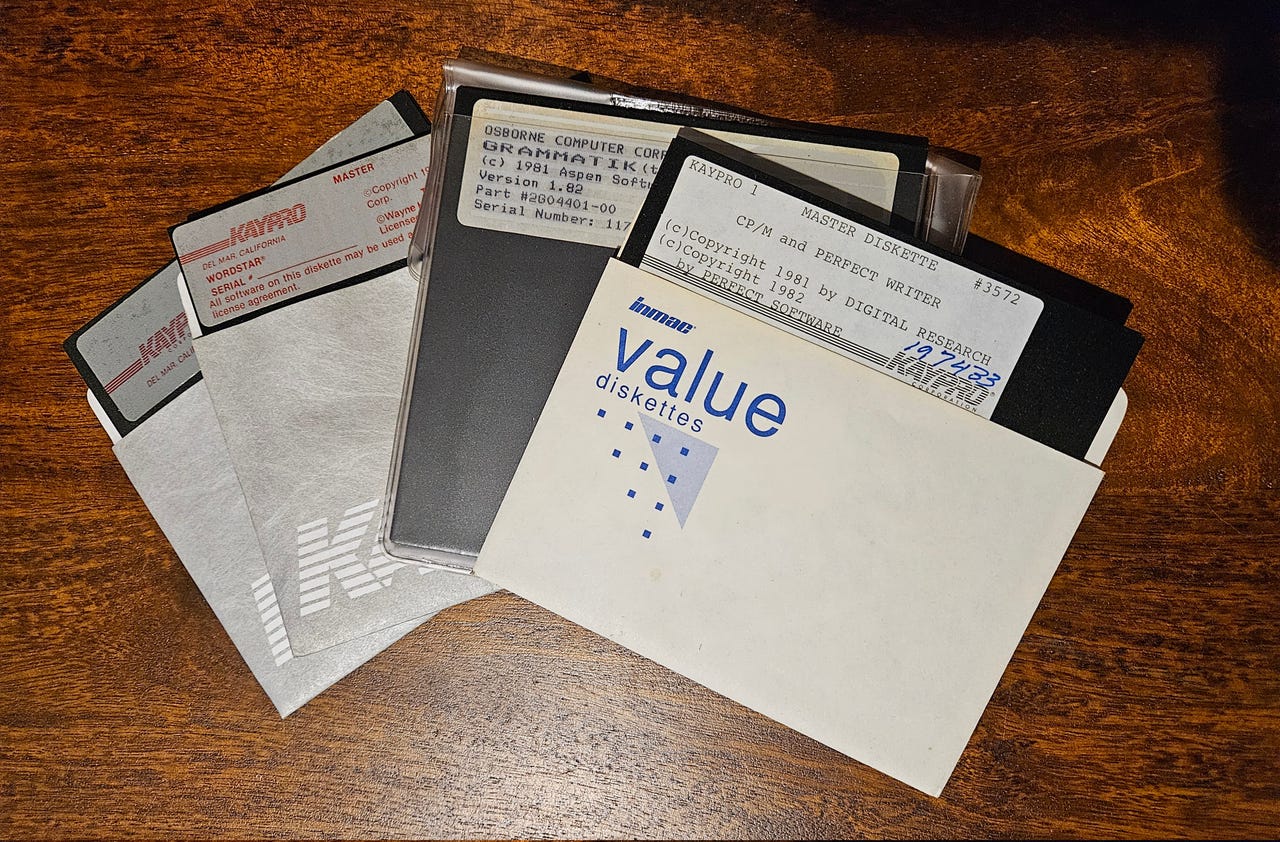

A few of 5.35″ floppy disks from the early 80s.

sjvn

I don’t remember when I first started using a floppy disk in the mid-70s. It was either installing firmware on IBM S/370 mainframes or on a dedicated library workstation to create Library of Congress catalog records. Oh, the exciting life I’ve led! In either case, it would have been a single-sided, 8-inch floppy disk, which held an amazing 79.7 KiloBytes (KB) of data.

Hey, trust me, that was a big deal then when our other portable storage choices were IBM 12-row/80-column punched cards or 9-track tape. They were, in a word, cumbersome.

Also: BASIC turns 60: Why simplicity was this programming language’s blessing and its curse

Floppy disks predated me getting my feet wet in computing. In the late 1960s, IBM engineers Alan Shugart and David L. Noble envisioned a compact and portable solution for storing data. This pioneering work, Project Minnow, led to the creation of the first commercially viable 8-inch floppy disk in 1971. Its 79K of storage may seem like nothing to you, but it held the equivalent of 3,000 punched cards.

Which would you rather drop? A single disk or thousands of cards? Yeah, that’s what we all thought, too.

As personal computers gained popularity in the 1970s, the floppy disk moved from my world of mainframes and workstations to PCs. There, it found its place as an affordable and accessible storage solution.

Then, in 1976, a guy named Steve Wozniak wanted to add a floppy drive to his next computer. His buddy, Steve Jobs, got a 5.25-inch floppy disk from Shugart’s new company, Shugart Associates, in 1976, and after a lot of hacking, Woz got the first floppy drive to run on what would become the Apple II.

These new-fangled disks first held from 90 to 110KB. Then floppy disks were upgraded first to 160KB and then 360KB, which is what many of us think of as their default size. That is until the 1.2Megabyte (MB) size disks appeared in 1984 along with the IBM/AT PC. We loved those disks and that blazingly fast 6MHz computer.

Also: Dell turns 40: How a teenager transformed $1,000 worth of PC parts into a tech giant

From then on, the floppy disk took off. With the ability to distribute programs on these portable disks, software companies could now sell their products through mail or retail stores. The first software markets sprang from floppy disks.

It wasn’t just major companies, either. Floppy disks enabled anyone to create and sell programs, which sparked the freeware and shareware movements. They also enabled people to share data easily for the first time. Long before we were using modems and Bulletin Board Systems (BBS) to share programs, pictures, and data, we would share them by “sneakerware.” That is, literally walking the information from one computer to another by hand carrying disks.

In 1981, Sony introduced the 3.5-inch floppy disk. It quickly gained popularity due to its smaller size and higher storage capacity compared to its predecessors. It was also much more stable than the earlier models. They’d had a habit of going bad all too quickly with wear and tear.

Also: The Mac turns 40: How Apple’s rebel PC almost failed again and again

Although no longer “floppy,” this format became the standard for floppy disks. Its popularity lasted well into the 1990s, solidifying the floppy disk’s position as a ubiquitous storage medium. This design started with 720KB of storage, but its most popular version held 1.44MB.

As computer networking and new storage formats like USB flash drives and memory cards emerged, the floppy disk’s reign waned in the mid-to-late 1990s. The end of the floppy disk era came with the introduction of the floppy-less iMac in 1998.

By the early 2000s, floppy disks had become increasingly rare, used primarily with legacy hardware and industrial equipment. Sony manufactured the last new floppy disk in 2011.

Despite its obsolescence, the floppy disk’s legacy endures. Its iconic design has become a symbol of data storage, and the floppy disk icon still appears on many computer desktops as the file-saving symbol.

But as obsolete as its technology may seem, the floppy disk is still used today. For example, industrial embroidery machines from the 1990s were built to read patterns and designs from floppy disks. Some older industrial machines and equipment, like computer numerical control (CNC) machines, still use floppy disks to load software updates and programs.

Also: You know Apple’s origin story but do you know Samsung’s? It’s almost too bonkers to believe

Some older Boeing 747 models still use floppy disks to load critical navigation database updates and software into their avionics systems. Indeed, Tom Persky, the president of floppydisk.com, which sells and recycles floppy disks, said in 2022 that the airline industry remains one of his biggest customers.

Closer to the ground, in San Francisco, the Muni Metro light railway, which launched in 1980, won’t start up each morning unless its Automatic Train Control System staff is booted up with a floppy. Why? It has no hard drive and it’s too unstable to be left on, so every morning, in goes the disk, and off goes the trains. It will be replaced, though… eventually. Currently, the updated replacement project is scheduled to be completed in 2033/4.

Floppy drives also live on in medical devices such as CT scanners and ultrasound machines. Famously, or infamously, until 2019, the US nuclear missile sites force still used 8-inch floppy disks as part of the system for coordinating operational components. On a far more amusing note, those Chuck E. Cheese’s animatronic figures you saw at your eighth birthday party? Yep, they’re driven by floppy disks.

Also: The best NAS devices of 2024

And, of course, some people, such as musician Espen Kraft, still use floppy disks with older synthesizers and samplers to load sounds and create music. He’s not alone; other collectors and retro computing enthusiasts continue to use and trade floppy disks to this day.

Why do they linger? As Persky told NPR, they’re “extremely stable, extremely well-understood, not really hackable, and perform an unbelievably great job for very small bits of data.”

Well, that’s part of it. But, another part is technical debt. Some of those machines where floppies live are extremely expensive. So long as they keep running, and you can find fresh floppies to use on them as the old ones wear out, no one wants to pay to replace them. In some more extreme cases, no replacement machinery is available for the old hardware.

Eventually, they’ll all have to replace their old kit. But, it won’t surprise me a bit when, by the time I shuffle off this mortal coil, someone, somewhere, will still be running a floppy drive in a production system.

+ There are no comments

Add yours