Getty Images

Crooks are working overtime to anonymize their illicit online activities using thousands of devices of unsuspecting users, as evidenced by two unrelated reports published Tuesday.

The first, from security firm Lumen Labs, reports that roughly 40,000 home and office routers have been drafted into a criminal enterprise that anonymizes illicit Internet activities, with another 1,000 new devices being added each day. The malware responsible is a variant of TheMoon, a malicious code family dating back to at least 2014. In its earliest days, TheMoon almost exclusively infected Linksys E1000 series routers. Over the years it branched out to targeting the ASUS WRTs, VIVOTEK Network Cameras, and multiple D-Link models.

In the years following its debut, the TheMoon’s self-propagating behavior and growing ability to compromise a broad base of architectures enabled a growth curve that captured attention in security circles. More recently, the visibility of the Internet-of-things botnet trailed off, leading many to assume it was inert. To the surprise of researchers in Lumen’s Black Lotus Lab, during a single 72-hour stretch earlier this month, TheMoon added 6,000 ASUS routers to its ranks, an indication that the botnet is as strong as it’s ever been.

More stunning than the discovery of more than 40,000 infected small office and home office routers located in 88 countries is the revelation that TheMoon is enrolling the vast majority of the infected devices into Faceless, a service sold on online crime forums for anonymizing illicit activities. The proxy service gained widespread attention last year following this profile by KrebsOnSecurity.

“This global network of compromised SOHO routers gives actors the ability to bypass some standard network-based detection tools—especially those based on geolocation, autonomous system-based blocking, or those that focus on TOR blocking,” Black Lotus researchers wrote Tuesday. They added that “80 percent of Faceless bots are located in the United States, implying that accounts and organizations within the US are primary targets. We suspect the bulk of the criminal activity is likely password spraying and/or data exfiltration, especially toward the financial sector.”

The researchers went on to say that more traditional ways to anonymize illicit online behavior may have fallen out of favor with some criminals. VPNs, for instance, may log user activity despite some service providers’ claims to the contrary. The researchers say that the potential for tampering with the Tor anonymizing browser may also have scared away some users.

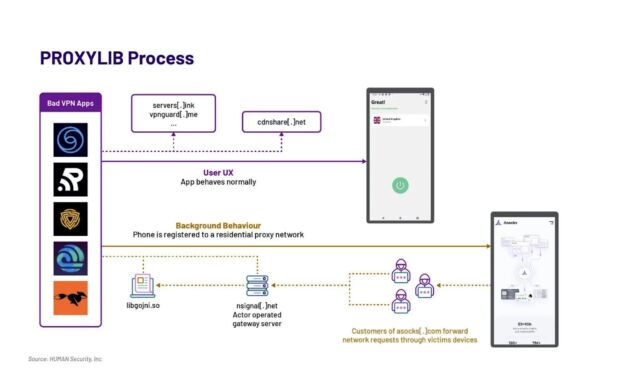

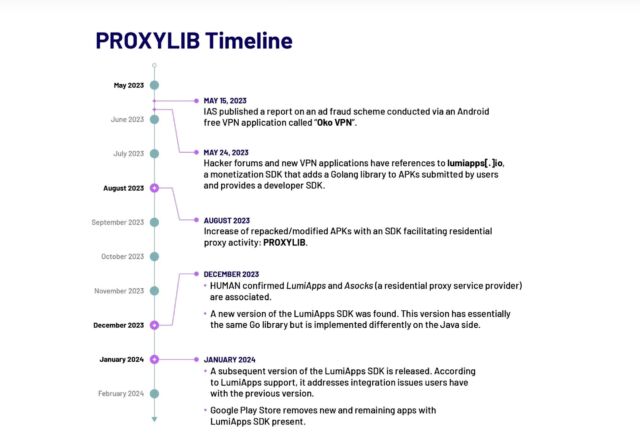

The second post came from Satori Intelligence, the research arm of security firm HUMAN. It reported finding 28 apps available in Google Play that, unbeknownst to users, enrolled their devices into a residential proxy network of 190,000 nodes at its peak for anonymizing and obfuscating the Internet traffic of others.

HUMAN

ProxyLib, the name Satori gave to the network, has its roots in Oko VPN, an app that was removed from Play last year after being revealed using infected devices for ad fraud. The 28 apps Satori discovered all copied the Oko VPN code, which made them nodes in the residential proxy service Asock.

HUMAN

The researchers went on to identify a second generation of ProxyLib apps developed through lumiapps[.]io, a software developer kit deploying exactly the same functionality and using the same server infrastructure as Oko VPN. The LumiApps SDK allows developers to integrate their custom code into a library to automate standard processes. It also allows developers to do so without having to create a user account or having to recompile code. Instead they can upload their custom code and then download a new version.

HUMAN

“Satori has observed individuals using the LumiApps toolkit in the wild,” researchers wrote. “Most of the applications we identified between May and October 2023 appear to be modified versions of known legitimate applications, further indicating that users do not necessarily need to have access to the applications’ source code in order to modify them using LumiApps. These apps are largely named as ‘mods’ or indicated as patched versions and shared outside of the Google Play Store.”

The researchers don’t know if the 190,000 nodes comprising Asock at its peak were made up exclusively of infected Android devices or if they included other types of devices compromised through other means. Either way, the number indicates the popularity of anonymous proxies.

People who want to prevent their devices from being drafted into such networks should take a few precautions. The first is to resist the temptation to keep using devices once they’re no longer supported by the manufacturer. Most of the devices swept into TheMoon, for instance, have reached end-of-life status, meaning they no longer receive security updates. It’s also important to install security updates in a timely manner and to disable UPnP unless there’s a good reason for it remaining on and then allowing it only for needed ports. Users of Android devices should install apps sparingly and then only after researching the reputation of both the app and the app maker.

+ There are no comments

Add yours