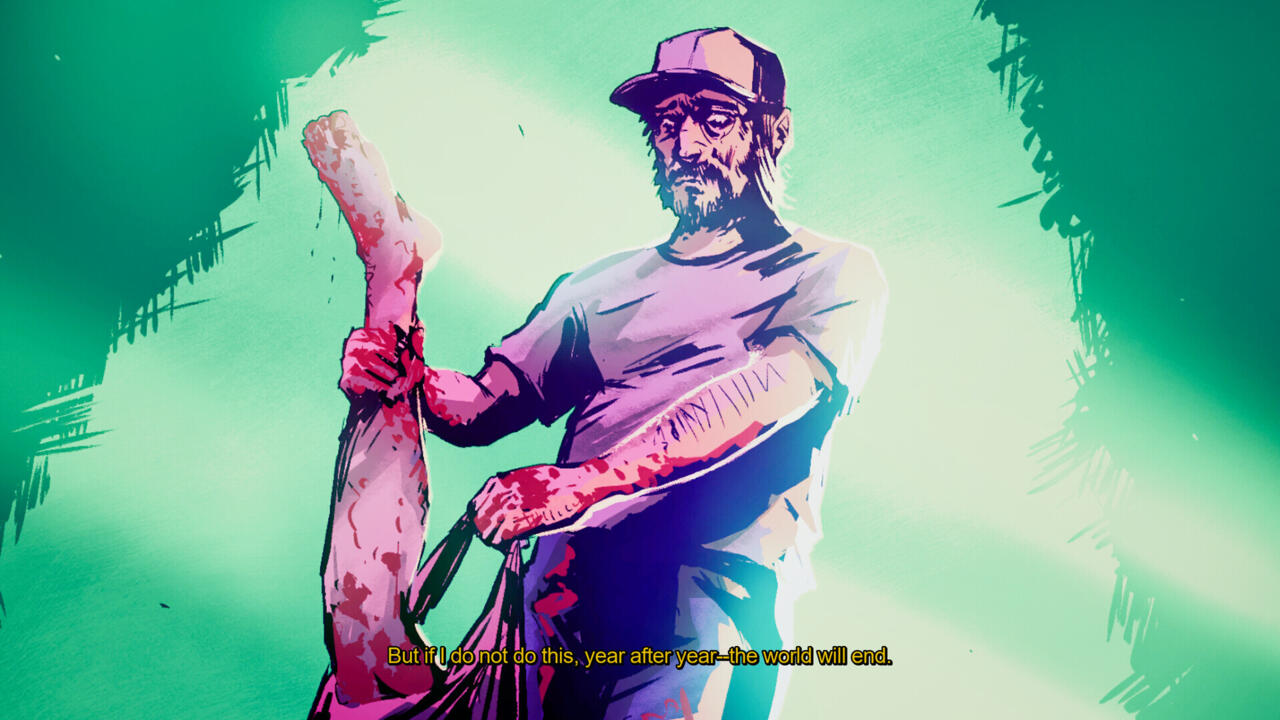

Of all the games I sat down to talk about at GDC 2024, none left quite as much of an impression as Life Eater, an upcoming kidnapper simulator. The game is developed by Strange Scaffold, the studio that has pushed the envelope on what types of stories you can tell in a video game in the likes of titles like El Paso, Elsewhere and Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator. Life Eater looks incredibly creepy, tasking you to stalk targets in order to kidnap and sacrifice them to a god that promises that, should you fail, the world is doomed.

The game utilizes a lot of elements that I love in other games–tracking down targets and learning their patterns like in Hitman, listening to recordings to deduce the location and motives of different people like Unheard–while adding a dash of horror that challenges the player to contend with the increasingly rewarding voyeuristic patterns. I spoke to Strange Scaffold’s Xalavier Nelson Jr. about how Life Eater hopes to dig its claws into the player with its focus on self-reflection horror and how, as he puts it, “the best horror emerges from asking a fairly innocuous question.”

Life Eater is scheduled to launch for PC on April 16.

GameSpot: I have to ask: Why a kidnapper simulator? That can’t be a hugely marketable genre.

Nelson Jr.: Yeah, the joke is that we’re stepping into a crowded genre, because we aren’t, especially as we explore more and more design territory. There’s stuff that reminds you of it, things like the Hitman series. We have really interesting timeline-based games, even stuff like John Wick Hex. But for the kidnapping sim, the horror-fantasy kidnapping sim in particular, there’s nothing there. And the way that Strange Scaffold approaches its next projects is always a set of holistic questions. “Does this align with our values of making games better, faster, cheaper, and healthier than the industry as soon as possible?” [And] “Not just what game are we making, but how will we make it?” And “What are the things that we’re calling from and pulling it into?”

So when it came to choosing this project and this genre, it was realizing that there was an opportunity with this subject material to do a really nuanced and interesting game that hasn’t quite been done before, even if you’ve seen things like it. And whenever I see an opportunity like that, it’s really hard to turn it down.

How do you do research for something like this?

I think the best horror emerges from asking a fairly innocuous question. Paranormal Activity is asking the question, “What happens if your perception of reality is not matching up with what’s happening in your house, and you have a third party who can compare those two nights?” Poltergeist is an evil coming out of the television in the middle of the Satanic panic. There are always attacks [against the player] that [work best in] horror. Even John Carpenter’s The Thing. What if your co-worker isn’t your co-worker but something wearing his skin? That’s where it emerges. So for me, especially in today’s information culture, I grew up in an age on the internet where no one shared their real name online. No one shared their location. No one shared pictures of where they were when they were at that location.

Because the question is, if you take a picture of yourself outside of your home, that means you aren’t in your home. And we exist on a social contract that says no one will take advantage of that information, even though that can and does happen. So modern day society, one of the things that–a lot of it was not necessarily doing research into kidnapping, because kidnapping often happens… I think the specific [statistic] is something like [in] 90% of kidnappings, the perpetrator of the kidnapping is someone who the victim already knows. So a lot of what we did was just kind of look at the tools available in the modern day and ask the question of, “What if someone wanted to use this for harm?”

So a great example of this is geotags. If you have a geotag, you can put that anywhere technically including on someone else’s person, or in their car, or underneath the rim of their wheel.

That’s terrifying. I didn’t think about that before this moment.

That’s kind of the thing. And people have talked on social media about how this is a really dangerous thing, potentially, and ask the question of, “What if someone wanted to use that for harm?” was the basis for a lot of dark but interesting design questions. Another great example is the fake Amazon package scam, where you open up a package on your doorstep, and it’s supposedly from Amazon. And it has a ring camera in it. And people will often not report a ring camera or a toy that arrived at their front door, because they thought they got one over on Amazon. And they got a free package. Turns out, the person who dropped it off either has a backdoor exploit, or that footage is not going to Amazon. It’s going to them. Or that teddy bear has a camera inside of it.

And the fact that in all of our lives, we’ve got these little holes, the unobserved nooks and crannies from which something could be lurking, that’s the basis for an amazing horror, and it turns out a very interesting systemic gameplay space for a player.

I got somewhat of a nature, Druidic vibe from the trailer. How does that inform the message of this horror?

It isn’t necessarily nature, but there’s definitely the idea of being held hostage by God. I’m always interested in exploring relationship dynamics in my game. So in Airport for Aliens Currently Run by Dogs, there’s a Black love story at the end of the world.

El Paso, Elsewhere was the relationship of an abuse survivor, but also had a strong masculine Black video game protagonist and the nuances of what it means to recover from relationship abuse and trauma. Sunshine Shuffle kind of deals with interesting surrogate father dynamics and found family. And for Life Eater, it’s this situation of someone being held hostage by God. In this case, a dark god, Zimforth. But when the deity you serve doesn’t have your best interests at heart and is more interested in actually harming you than any collateral damage you might cause, again, it exposes gameplay scenarios that let the player walk away and feel something, as opposed to just kind of having horror for the sake of it.

We’re in a golden age of horror right now. Poppy’s Playtime, Bendy. There’s a lot of things that end in ‘y’. There’s a lot of fun, happy creatures where something horrible happens, and those are really worthwhile games as well. I trust in players to want the type of horror that says, “In your life, what’s a system that you feel differently about because you had it mirrored to you in a video game?”

And we knew that what we were doing with Life Eater worked when we were doing our first play test, and we realized how interesting it was to learn about a fictional person. Didn’t even care about how or why, but realizing that this person goes to the bathroom three times in the middle of the night and the kind of invasive nature of that and how much we as human beings, as far as social media, is our compulsion to look at each other.

You just want to know, and the reason you want to know, in this case, is your curiosity is turned into the engine that allows for horrible things to happen.

Why are you psychologically attacking me with your video game?

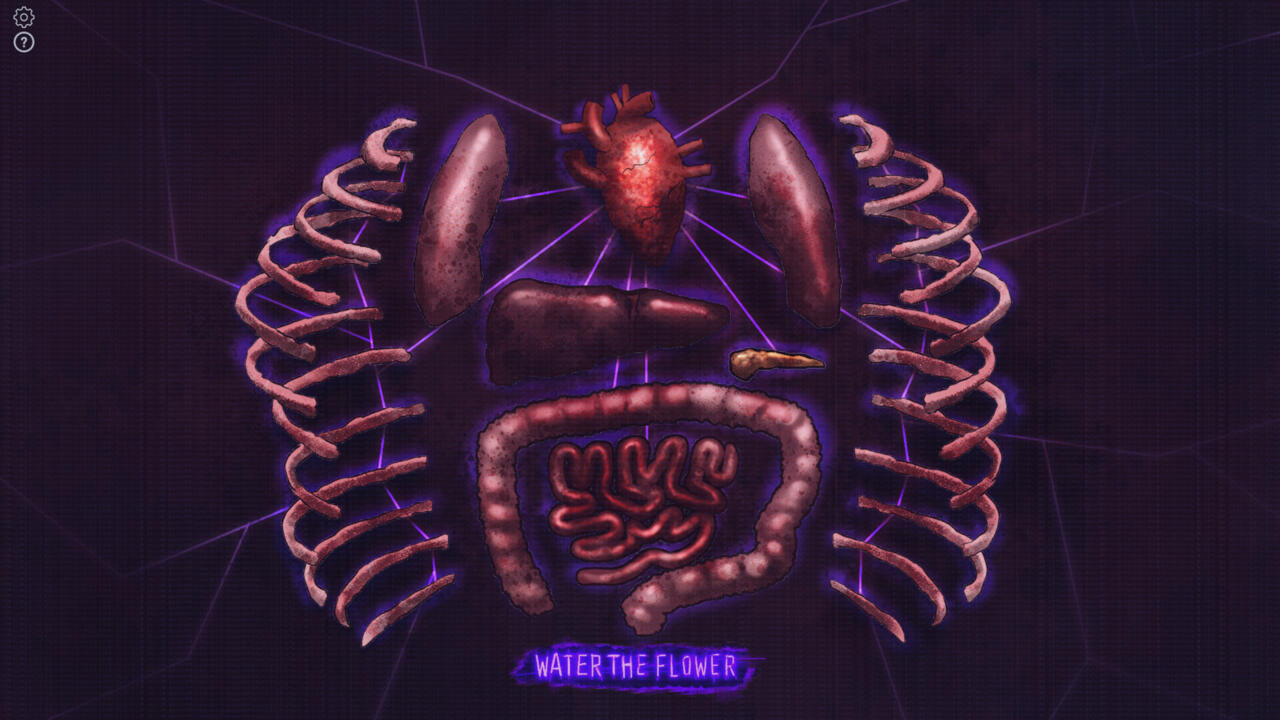

Because…I don’t know. It’s 2024, and I feel like I’ve got plenty of media that I can just veg out to and release any sensation or expectation of outside of anything being entertained. But I want something to shake me. I like things now that fuck me up. And there was a period of time where I wasn’t looking for that, but as more and more media feels afraid to genuinely push you into an uncomfortable place, I think Life Eater and Space Warlord Organ Trading Simulator asking the very deliberate question of, “How do you not care about the fact that you’re just buying and selling organs when it makes a number go up?” That is the type of experience that also speaks to me. I make this, because these are the games that I love to play as a player.

There’s a fantastic series called Rusty Lake. It was a Flash game series called Cube Escape, and then they became the Rusty Lake series. And so there’s Rusty Lake Hotel and Underground Blossom and all this anthology of games that are all about deliberate adventure game dream logic. And they all end in two to three hours, and they’re like three, four or five bucks each. It’s like you realize that you’re trying to plunge into a circle, and then you find a scalpel. And you realize that this person’s nipple is a circle. And then you put the scalpel on the nipple, and it carves it open. And then you plunge into their body.

It’s a very simple chain of logic. When you realize that you’re following the chain of inevitable, horrible things, there’s nothing like it. And there are games I play just to have fun, but, as a player, when I can have fun and also feel something, get shaken up, go on a journey, no matter how long that game is, I get to carry something away from it. And I think that lasts a lot longer than a video game with a 400-hour play time, especially these days.

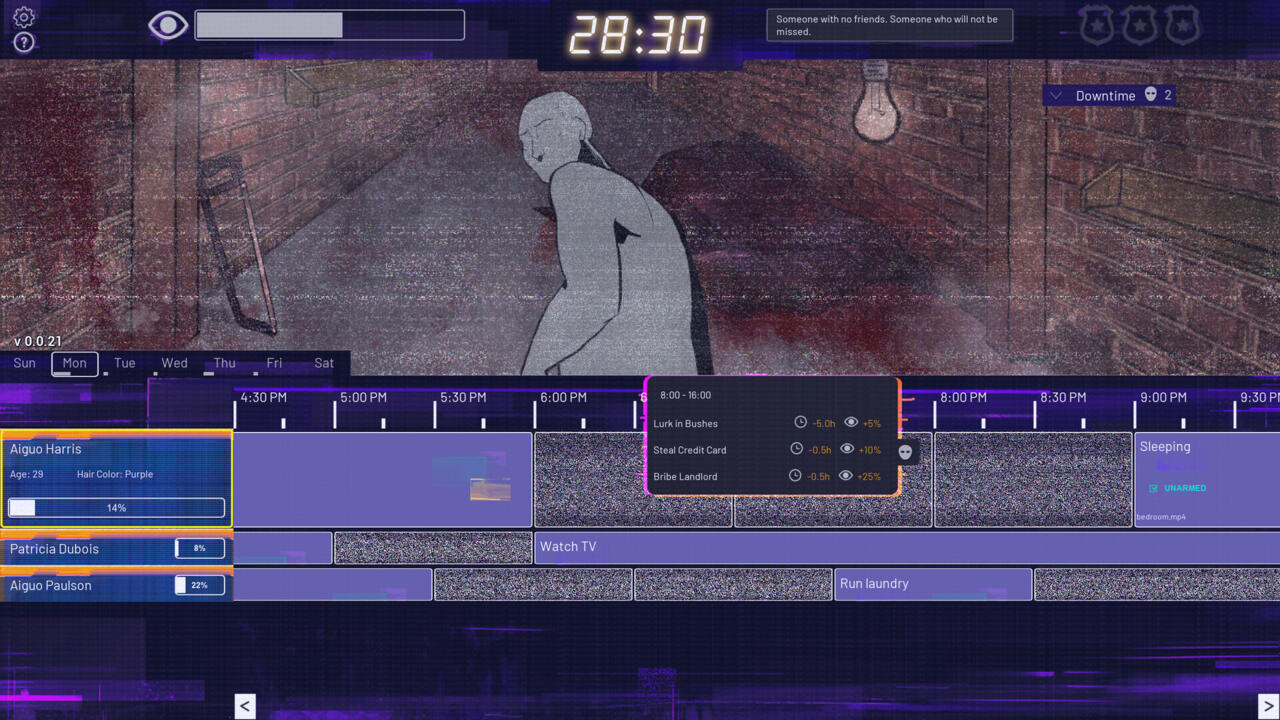

Describe to me the moment-to-moment gameplay. Are you just watching people? Are you actually moving around and going to people’s houses?

So it’s an analog horror interface game. You’re presented with the objective for the year. Zimforth has you kidnap and murder people to delay the end of the world–[you’re doing this] on behalf of this god that you aren’t fully sure exists. But what Zimforth demands is not just that you find a target, but that you find a specific target that is often vaguely worded.

One of the objectives in the game is that you have to find a pair of siblings, and Zimforth gives you four names. And you are looking through these names and trying to figure out just by their schedules and how they live their lives, by clicking on pieces of their timeline and then doing increasingly invasive things to investigate it. So level-two actions to try to investigate space and see if that is enough risk and time spent in order to find that piece of information. You’re unraveling their timelines bit by bit to try to find, “Who are the siblings here that Zimforth wants me to sacrifice?

Another scenario is that Zimforth wants you to eliminate someone who is terminally ill, but they’re always surrounded by both a caretaker as well as a family member. So you’re trying to find, by exploring the lives of the people around them, the one space in which they’re alone.

That’s really cool. Creepy as hell, but really cool.

[They are] these really creepy as hell, nuanced puzzles. Yeah, we hope that they stick with players for a long time if only because there’s not many games exploring this space. It was a crowded genre in the 2000s, alongside World War II horror games. It was World War II shooters and kidnapping sims [that] were all the rage in the 2000s, and we’re bringing it back. For too long, this genre has remained stagnant: the boomer shooter and the boomer kidnapper.

What’s it like to play this game a second time?

So in the central story mode, the situations are very bespoke, but we both have a post-game period, where you’re given procedurally generated targets and scenarios as well as post-launch, we’re looking at the endless mode, for those who are interested to continuing to reap the field of harvest for Zimforth. Yeah. Basically post-launch, we will have a post-game and an endless mode that give you endless, devious little puzzles to engage in if someone so chooses. But the story mode, it’s very much a bespoke experience.

The way I’ve discussed it with the team is that I want that endless mode, which is why we’re making it something that lands post-launch, because we want to do it right. And we want to do the story mode justice. So yeah, story mode… Sorry. Endless mode and post-game both come this March. But yeah, the thing I compared it to is Murder Sudoku.

If someone wants to open up a little Murder Sudoku and get told, “In this group of people, find the person who urinates the most” and use a series of context clues in their schedule to figure out that solution, that’s something I give that players deserve to experience that the games industry, at large, is not giving.

This interview was edited for both brevity and readability.

+ There are no comments

Add yours