If you puncture the ovary of a wasp called Microplitis demolitor, viruses squirt out in vast quantities, shimmering like iridescent blue toothpaste. “It’s very beautiful, and just amazing that there’s so much virus made in there,” says Gaelen Burke, an entomologist at the University of Georgia.

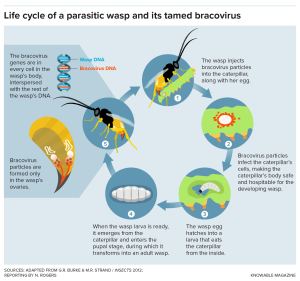

M. demolitor is a parasite that lays its eggs in caterpillars, and the particles in its ovaries are “domesticated” viruses that have been tuned to persist harmlessly in wasps and serve their purposes. The virus particles are injected into the caterpillar through the wasp’s stinger, along with the wasp’s own eggs. The viruses then dump their contents into the caterpillar’s cells, delivering genes that are unlike those in a normal virus. Those genes suppress the caterpillar’s immune system and control its development, turning it into a harmless nursery for the wasp’s young.

The insect world is full of species of parasitic wasps that spend their infancy eating other insects alive. And for reasons that scientists don’t fully understand, they have repeatedly adopted and tamed wild, disease-causing viruses and turned them into biological weapons. Half a dozen examples already are described, and new research hints at many more.

By studying viruses at different stages of domestication, researchers today are untangling how the process unfolds.

Partners in diversification

The quintessential example of a wasp-domesticated virus involves a group called the bracoviruses, which are thought to be descended from a virus that infected a wasp, or its caterpillar host, about 100 million years ago. That ancient virus spliced its DNA into the genome of the wasp. From then on, it was part of the wasp, passed on to each new generation.

Over time, the wasps diversified into new species, and their viruses diversified with them. Bracoviruses are now found in some 50,000 wasp species, including M. demolitor. Other domesticated viruses are descended from different wild viruses that entered wasp genomes at various times.

Researchers debate whether domesticated viruses should be called viruses at all. “Some people say that it’s definitely still a virus; others say it’s integrated, and so it’s a part of the wasp,” says Marcel Dicke, an ecologist at Wageningen University in the Netherlands who described how domesticated viruses indirectly affect plants and other organisms in a 2020 paper in the Annual Review of Entomology.

As the wasp-virus composite evolves, the virus genome becomes scattered through the wasp’s DNA. Some genes decay, but a core set is preserved—those essential for making the original virus’s infectious particles. “The parts are all in these different locations in the wasp genome. But they still can talk to each other. And they still make products that cooperate with each other to make virus particles,” says Michael Strand, an entomologist at the University of Georgia. But instead of containing a complete viral genome, as a wild virus would, domesticated virus particles serve as delivery vehicles for the wasp’s weapons.

Those weapons vary widely. Some are proteins, while others are genes on short segments of DNA. Most bear little resemblance to anything found in wasps or viruses, so it’s unclear where they originated. And they are constantly changing, locked in evolutionary arms races with the defenses of the caterpillars or other hosts.

In many cases, researchers have yet to discover even what the genes and proteins do inside the wasps’ hosts or prove that they function as weapons. But they have untangled some details.

For example, M. demolitor wasps use bracoviruses to deliver a gene called glc1.8 into the immune cells of moth caterpillars. The glc1.8 gene causes the infected immune cells to produce mucus that prevents them from sticking to the wasp’s eggs. Other genes in M. demolitor’s bracoviruses force immune cells to kill themselves, while still others prevent caterpillars from smothering parasites in sheaths of melanin.

+ There are no comments

Add yours