In 2018, a team of French physicists developed a rudimentary mathematical model to describe the deformation of a common type of knit. Their work was inspired when co-author Frédéric Lechenault watched his pregnant wife knitting baby booties and blankets, and he noted how the items would return to their original shape even after being stretched. With a few colleagues, he was able to boil the mechanics down to a few simple equations, adaptable to different stitch patterns. It all comes down to three factors: the “bendiness” of the yarn, the length of the yarn, and how many crossing points are in each stitch.

A simpler stitch

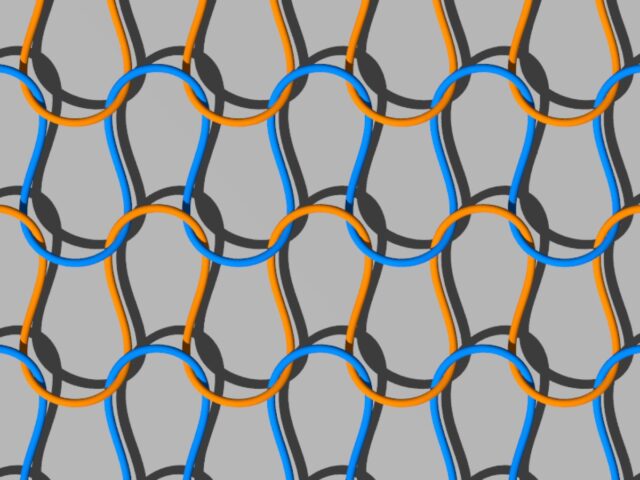

A simplified model of how yarns interact

Credit:

J. Crassous/University of Rennes

One of the co-authors of that 2018 paper, Samuel Poincloux of Aoyama Gakuin University in Japan, also co-authored this latest study with two other colleagues, Jérôme Crassous (University of Rennes in France) and Audrey Steinberger (University of Lyon). This time around, Poincloux was interested in the knotty problem of predicting the rest shape of a knitted fabric, given the yarn’s length by stitch—an open question dating back at least to a 1959 paper.

It’s the complex geometry of all the friction-producing contact zones between the slender elastic fibers that makes such a system to difficult to model precisely, because the contact zones can rotate or change shape as the fabric moves. Poincloux and his cohorts came up with their own more simplified model.

The team performed experiments with a Jersey stitch knit (aka a stockinette), a widely used and simple knit consisting of a single yarn (in this case, a nylon thread) forming interlocked loops. They also ran numerical simulations modeled on discrete elastic rods coupled with dry contacts with a specific friction coefficient to form meshes.

The results: Even when there were no external stresses applied to the fabric, the friction between the threads served as a stabilizing factor. And there was no single form of equilibrium for a knitted sweater’s resting shape; rather, there were multiple metastable states that were dependent on the fabric’s history—the different ways it had been folded, stretched, or rumpled. In short, “Knitted fabrics do not have a unique shape when no forces are applied, contrary to the relatively common belief in textile literature,” said Crassous.

DOI: Physical Review Letters, 2024. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.133.248201 (About DOIs).

+ There are no comments

Add yours