Dermatologists are sounding the alarm over two emerging types of fungi that can cause nasty bouts of ringworm. In a new report Wednesday, they describe the first known U.S. case of one ringworm fungus that can spread sexually, while another recent paper details the arrival of a species resistant to the most common antifungals used to treat these infections.

Ringworm, despite the name, has nothing to do with parasitic worms. It’s instead a reference to the circular rashes often caused by certain fungal infections of the skin. These infections are also known as tinea and can have additional nicknames depending on where along the body they’re found, such as athlete’s foot and jock itch for infections near the armpits or groin.

There are about 40 different species of fungi that can cause ringworm. These infections are typically mild (if very itchy) and treatable with antifungals. But in recent years, dermatologists in Asia, Europe, and most recently the U.S. have started to see ringworm infections that are a bit stranger and hardier than usual.

Avrom Caplan, a doctor specializing in autoimmune disorders of the skin at New York University, and his colleagues recently came across one of these cases. Their patient, a man in his 30s, developed scaly, circular rashes directly on and surrounding his genitals. Initial testing identified the man’s fungus as a species that typically causes athlete’s foot or fungal toenail infections, but genetic sequencing revealed that it was actually the emerging fungus Trichophyton mentagrophytes ITS genotype VII, or TMVII.

TMVII has previously been detected in parts of Europe, and it may be spreading predominantly through sexual contact—something only rarely seen with other causes of ringworm. A paper looking at 13 TMVII cases in France, published last year, found evidence of sexual transmission in nearly all cases. These cases all involved men, with 12 reporting that they regularly had sex with men. Other research has traced the emergence of TMVII to southeast Asia, where its initial spread may have been aided by contact with infected sex workers.

The French paper was actually what led Caplan and his colleagues to be on the lookout for TMVII in the first place. And sure enough, it didn’t take long for them to find a case on their radar. This latest case, published Wednesday in JAMA Dermatology, appears to be the first reported instance of TMVII within the U.S. and it features some of the same hallmarks as earlier ones. The patient reported having traveled recently to Europe and California as well as having had sex with multiple male partners during his trips.

“The takeaway for clinicians is that TMVII has arrived in the U.S., and we should be aware of it,” Caplan told Gizmodo.

Amazingly, this is the second emerging fungi that Caplan has crossed paths with as of late. Last May, he and other researchers, including local and CDC health officials, detailed the first known cases of Trichophyton indotineae in the U.S. This past May, Caplan and others wrote a paper about these and other cases discovered recently in New York City.

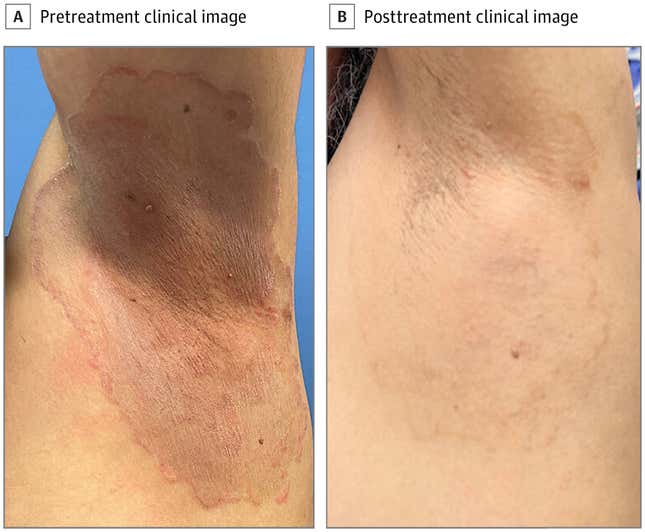

T. indotineae, which likely first emerged in India, is worrying for several reasons. For one, it tends to cause more severe ringworm, with itchy, sometimes atypical, rashes all over the body that could be confused for eczema. Secondly, topical over-the-counter antifungal creams typically don’t work on it. The fungus also frequently resists the frontline medication terbinafine, even when taken orally, and often resists two other oral medications, fluconazole and griseofulvin. There is one medication that appears to reliably work for the time being, itraconazole, but the treatment can take eight weeks or longer to fully clear the infection, and it can interact badly with other common drugs. If that isn’t bad enough, the fungi also seems capable of being sexually transmitted.

“So between the significant quality of life impact, potential to spread to other people, the typical failure of oral first-line antifungal medications, and the long treatment duration required with an oral antifungal, it’s very concerning, and different than the more common ringworm people may have, which is often treated with over-the-counter topical antifungal creams,” Caplan said.

We know less about TMVII for now, but it too seems more difficult to treat than the usual ringworm. Caplan’s patient failed to respond to an initial four-week course of fluconazole, though he did improve after six weeks of terbinafine. Ultimately, the patient was switched to a course of itraconazole, which appeared to clear the infection for good, Caplan said (the patient is still being monitored just to make sure).

At least for the time being, these emerging fungi aren’t an urgent public health concern within the U.S. Importantly, the team hasn’t found evidence that TMVII or T. indotineae have become endemic in the area. But we do need more research to better understand these new and other fungal threats, Caplan said.

Currently, for instance, it’s not possible to tell exactly how resistant these fungi are to a particular drug from lab results alone, the way doctors sometimes can with other types of infections. This lack of information can then drag out a patient’s treatment course. The team is also hoping their work can push fellow dermatologists to know about these fungi in the first place. Both TMVII and T. indotineae can be mistaken for other common sources of ringworm with conventional testing, which can further delay appropriate treatment and prolong a patient’s suffering.

Caplan and others are working with public health officials and the American Academy of Dermatology to spread the news about these fungi and to develop readily available resources on how to diagnose and treat these infections effectively.

“There are a lot of really amazing people working on these problems, so even though these infections are concerning, there is a concerted effort to tackle them,” Caplan said.

+ There are no comments

Add yours