NASA TV

Following weeks of speculation NASA finally made it official on Saturday: two astronauts who flew to the International Space Station on Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft in June will not come home on that vehicle. Instead, the agency has asked SpaceX to use its Crew Dragon spacecraft to fly astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams back to Earth.

“NASA has decided that Butch and Suni will return with Crew-9 next February,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson at the outset of a news conference on Saturday afternoon at Johnson Space Center.

In a sign of the gravity surrounding the agency’s decision, both Nelson and NASA’s deputy administrator, Pam Melroy, attended a Flight Readiness Review meeting held Saturday in Houston. During that gathering of the agency’s senior officials, an informal go-no go poll of those present was taken. Those present voted unanimously for Wilmore and Williams to return to Earth on Crew Dragon. The official recommendation of the Commercial Crew Program was the same, and Nelson accepted it.

Therefore Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft will undock from the station early next month—the tentative date, according to a source, is September 6—and attempt to make an autonomous return to Earth and land in a desert in the southwestern United States.

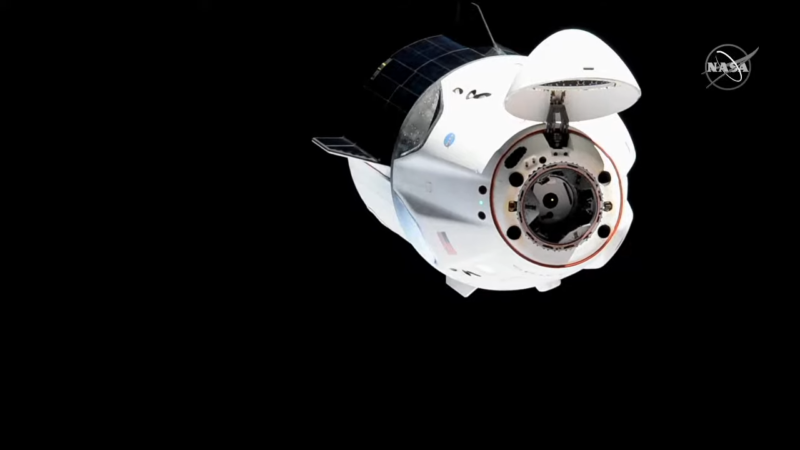

Then, no earlier than September 24, a Crew Dragon spacecraft will launch with two astronauts (NASA has not named the two crew members yet) to the space station with two empty seats. Wilmore and Williams will join these two Crew-9 astronauts for their previously scheduled six-month increment on the space station. All four will come back to Earth on the Crew Dragon vehicle about six months from now.

Saturday’s announcement has myriad implications for Boeing, which entered NASA’s Commercial Crew Program more than a decade ago and lent legitimacy to NASA’s efforts to pay private companies for transporting astronauts to the International Space Station. The company’s failure—and despite the encomiums from NASA officials during Saturday’s news conference, this Starliner mission is a failure—has myriad implications for Boeing’s future in spaceflight. Ars will have additional coverage of Starliner’s path forward later today.

Never could get comfortable with thruster issues

For weeks after Starliner’s arrival at the space station in early June, officials from Boeing and NASA expressed confidence in the ability of the spacecraft to fly Wilmore and Williams home. They said they just needed to collect a little more data on the performance of the vehicle’s reaction control system thrusters. Five of these 28 small thrusters that guide Starliner failed during the trip to the space station.

Engineers from Boeing and NASA tested the performance of these thrusters at a facility in White Sands, New Mexico, in July. Initially, the engineers were excited to replicate the failures observed during Starliner’s transit to the space station. Replicating failures is a critical step to understanding the root cause of a hardware problem.

However, what NASA found after taking apart the failed thrusters was concerning, said the chief of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program, Steve Stich.

“I would say the White Sands testing did give us a surprise,” Stich said Saturday. “It was this piece of Teflon that swells up, and got in the flow path and causes the oxidizer to not go into the thruster the way it needs to. That’s what caused the degradation of thrust. When we saw that, I think that’s when things changed a bit for us.”

When NASA took this finding to the thruster’s manufacturer, Aerojet Rocketdyne, the propulsion company said it had never seen this phenomenon before. It was at this point that agency engineers started to believe that maybe it would not be possible to identify the root cause of the problem in a timely manner, and become comfortable enough with the physics to be sure that thruster problem would not occur during Starliner’s return to Earth.

Thank you for flying SpaceX

The result of this uncertainty is that NASA will now turn to the other commercial crew provider, SpaceX. This is not a pleasant outcome for Boeing which, a decade ago, looked askance at SpaceX as something akin to space cowboys. I have covered the space industry closely during the last 15 years, and during most of that time Boeing was perceived by much of the industry as the blueblood of spaceflight, and SpaceX was the company that was going to kill astronauts due to its supposed recklessness.

Now the space agency is asking SpaceX to, in effect, rescue the Boeing astronauts currently on the International Space Station.

It won’t be the first time that SpaceX has helped a competitor recently. In the last two years SpaceX has launched a low-Earth orbit internet competitor’s satellites, OneWeb, after Russia’s space program squeezed the company; it has launched Europe’s sovereign Galileo satellites after delays to the Ariane 6 rocket; and it has launched NASA’s other space station cargo services provider, Northrop Grumman’s Cygnus spacecraft, multiple times. Now it well help a crew competitor, Boeing, out.

After Saturday’s news conference I asked Jim Free, NASA’s highest ranking civil servant, what he made of the once-upstart SpaceX now helping to backstop the rest of the Western spaceflight community. Without SpaceX, after all, NASA would not have a way to get crew or cargo to the International Space Station.

“They’re flying a lot, and they’re having success,” he said. “And you know, when they have an issue, they find a way to recover like with the second stage issue, We set out to have two providers to take crew to station to have options, and they’ve given us the option. In the reverse, Boeing could have been out there, and we still would face the same thing if they had a systemic Dragon problem, Boeing would have to bring us back. But I can’t argue with how much they’ve flown, that’s for sure, and what they’ve flown.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours