It took 20 years, but the design and delivery of the International Fusion Energy Project’s massive toroidal magnets is complete. The 19 coils are now in Southern France, according to an ITER release, setting the stage for the massive nuclear fusion project to make its first plasma… eventually.

ITER is a 35-nation collaboration to build a tokamak that will test the feasibility of nuclear fusion as an energy source. A tokamak is a doughnut-shaped container that holds a burning plasma fueled by fusion reactions.

Nuclear fusion is a reaction that occurs when two or more atoms’ light nuclei come together to form a single nucleus, releasing a huge amount of energy in the process. That’s not to be confused with nuclear fission, which releases energy and radioactive waste by splitting heavy nuclei apart. Nuclear fusion occurs naturally—it’s the reaction that powers stars—but not on Earth. However, physicists and engineers can induce nuclear fusion in laboratory settings, in tokamaks and using lasers. Silly as it sounds, that’s not the hard part. The real trick is facilitating fusion reactions that produce more energy than they take to catalyze, in theory producing limitless energy.

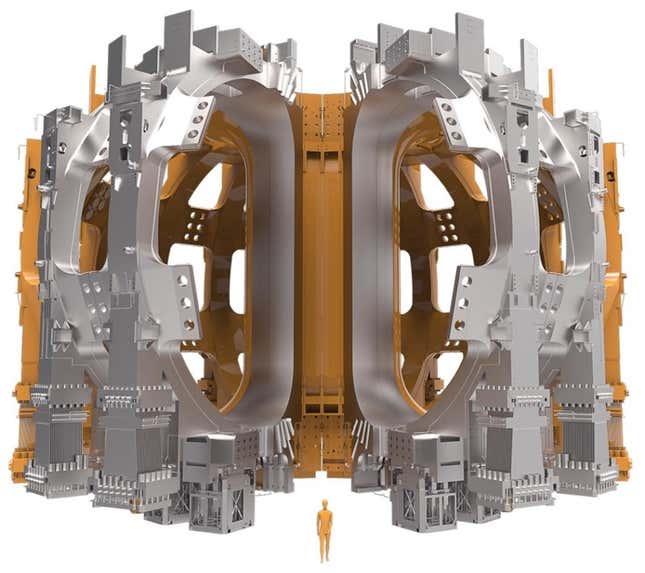

Tokamaks use magnets to contain and control their plasmas. ITER’s toroidal field coils—the experiment’s magnets—will be cooled to just -452.2 degrees Fahrenheit (-269 degrees Celsius), making them superconductive. The 56-foot tall (17-meter) coils will be wrapped around the doughnut-shaped vessel that contains the plasma, allowing ITER scientists to control the fusion within the vacuum vessel.

ITER will be larger than any other tokamak, with a central solenoid magnet made up of six 110-ton magnet modules. The entire tokamak will weigh a staggering 23,000 tons, and its magnets will generate a field about 300,000 times more powerful than the one generated by our whole freakin’ planet. Its plasma will be heated to 302 million degrees Fahrenheit (150 million degrees Celsius), 10 times hotter than the Sun’s core. ITER was expected to hold its first plasma next year, with its first fusion reaction slated for 2035, according to an updated baseline presented at the 34th ITER Council last month. The updated baseline schedule will be publicly announced in a press conference this Wednesday, July 3.

ITER was introduced by Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan in 1985, though the project was only sited in 2005. Nearly 20 years later, experiments have yet to be hosted in the tokamak. As reported by Scientific American, ITER’s cost has swelled fourfold since it began, with recent estimates putting the project at over $22 billion; technical defects and the covid pandemic have contributed to the delays.

A wry truism—so rehashed it’s a cliché—holds that nuclear fusion as an energy source is always 50 years away. It’s forever just beyond the technologies of today, and, like an irredeemable ex, we’re always told “this time it will be different.” ITER is intended to prove fusion power’s technological feasibility, but importantly not its economic viability. That’s another vexing issue: making fusion power not only a workable energy source, but a viable one for the power grid.

Nuclear fusion is seen as a holy grail of energy physics, a way to end our dependence on fossil fuels. But it will not come soon enough to address the worsening climate crisis. In other words, even if ITER demonstrates a massive breakthrough on the engineering side, it’s only one part of the Gordian knot of a problem. Not to be a wet blanket about fusion—we are getting closer, as demonstrated by the National Ignition Facility’s technological breakeven back in 2022—but there’s still a long way to go.

+ There are no comments

Add yours