Anyone who has been surfing the web for a while is probably used to clicking through a CAPTCHA grid of street images, identifying everyday objects to prove that they’re a human and not an automated bot. Now, though, new research claims that locally run bots using specially trained image-recognition models can match human-level performance in this style of CAPTCHA, achieving a 100 percent success rate despite being decidedly not human.

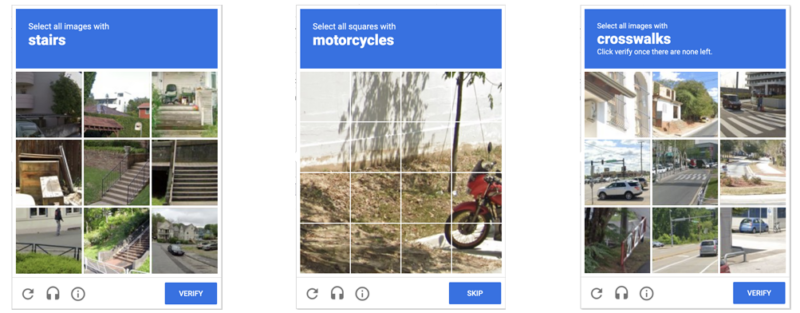

ETH Zurich PhD student Andreas Plesner and his colleagues’ new research, available as a pre-print paper, focuses on Google’s ReCAPTCHA v2, which challenges users to identify which street images in a grid contain items like bicycles, crosswalks, mountains, stairs, or traffic lights. Google began phasing that system out years ago in favor of an “invisible” reCAPTCHA v3 that analyzes user interactions rather than offering an explicit challenge.

Despite this, the older reCAPTCHA v2 is still used by millions of websites. And even sites that use the updated reCAPTCHA v3 will sometimes use reCAPTCHA v2 as a fallback when the updated system gives a user a low “human” confidence rating.

Saying YOLO to CAPTCHAs

To craft a bot that could beat reCAPTCHA v2, the researchers used a fine-tuned version of the open source YOLO (“You Only Look Once”) object-recognition model, which long-time readers may remember has also been used in video game cheat bots. The researchers say the YOLO model is “well known for its ability to detect objects in real-time” and “can be used on devices with limited computational power, allowing for large-scale attacks by malicious users.”

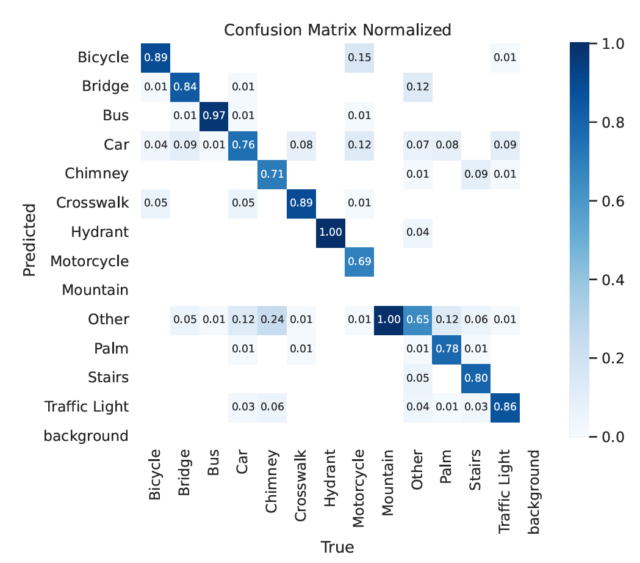

After training the model on 14,000 labeled traffic images, the researchers had a system that could identify the probability that any provided CAPTCHA grid image belonged to one of reCAPTCHA v2’s 13 candidate categories. The researchers also used a separate, pre-trained YOLO model for what they dubbed “type 2” challenges, where a CAPTCHA asks users to identify which portions of a single segmented image contain a certain type of object (this segmentation model only worked on nine of 13 object categories and simply asked for a new image when presented with the other four categories).

Beyond the image-recognition model, the researchers also had to take other steps to fool reCAPTCHA’s system. A VPN was used to avoid detection of repeated attempts from the same IP address, for instance, while a special mouse movement model was created to approximate human activity. Fake browser and cookie information from real web browsing sessions was also used to make the automated agent appear more human.

Depending on the type of object being identified, the YOLO model was able to accurately identify individual CAPTCHA images anywhere from 69 percent of the time (for motorcycles) to 100 percent of the time (for fire hydrants). That performance—combined with the other precautions—was strong enough to slip through the CAPTCHA net every time, sometimes after multiple individual challenges presented by the system. In fact, the bot was able to solve the average CAPTCHA in slightly fewer challenges than a human in similar trials (though the improvement over humans was not statistically significant).

The battle continues

While there have been previous academic studies attempting to use image-recognition models to solve reCAPTCHAs, they were only able to succeed between 68 to 71 percent of the time. The rise to a 100 percent success rate “shows that we are now officially in the age beyond captchas,” according to the new paper’s authors.

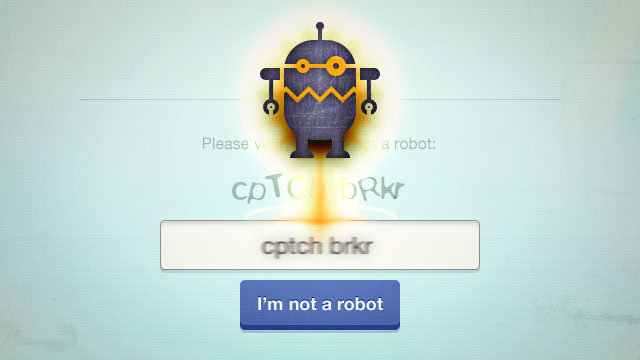

But this is not an entirely new problem in the world of CAPTCHAs. As far back as 2008, researchers were showing how bots could be trained to break through audio CAPTCHAs intended for visually impaired users. And by 2017, neural networks were being used to beat text-based CAPTCHAs that asked users to type in letters seen in garbled fonts.

Older text-identification CAPTCHAs have long been solvable by AI models.

Stack Exchange

Now that locally run AIs can easily best image-based CAPTCHAs, too, the battle of human identification will continue to shift toward more subtle methods of device fingerprinting. “We have a very large focus on helping our customers protect their users without showing visual challenges, which is why we launched reCAPTCHA v3 in 2018,” a Google Cloud spokesperson told New Scientist. “Today, the majority of reCAPTCHA’s protections across 7 [million] sites globally are now completely invisible. We are continuously enhancing reCAPTCHA.”

Still, as artificial intelligence systems become better and better at mimicking more and more tasks that were previously considered exclusively human, it may continue to get harder and harder to ensure that the user on the other end of that web browser is actually a person.

“In some sense, a good captcha marks the exact boundary between the most intelligent machine and the least intelligent human,” the paper’s authors write. “As machine learning models close in on human capabilities, finding good captchas has become more difficult.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours