SpaceX

Few people were happier with the successful outcome of last week’s test flight of SpaceX’s Starship launch system than a NASA engineer named Catherine Koerner.

In remarks after the spaceflight, Koerner praised the “incredible” video of the Starship rocket and its Super Heavy booster returning to Earth, with each making a soft landing. “That was very promising, and a very, very successful engineering test,” she added, speaking at a meeting of the Space Studies Board.

A former flight director, Koerner now manages development of the “exploration systems” that will support the Artemis missions for NASA—a hugely influential position within the space agency. This includes the Space Launch System rocket, NASA’s Orion spacecraft, spacesuits, and the Starship vehicle that will land on the Moon.

In recent months, NASA officials like Koerner have been grappling with the reality that not all of this hardware is likely to be ready for the planned September 2026 launch date for the Artemis III mission. In particular, the agency is concerned about Starship’s readiness as a “Human Landing System.” While SpaceX is pressing forward rapidly with a test campaign, there is still a lot of work to be done to get the vehicle down to the lunar surface and safely back into lunar orbit.

A spare tire

For these reasons, as Ars previously reported, NASA and SpaceX are planning for the possibility of modifying the Artemis III mission. Instead of landing on the Moon, a crew would launch in the Orion spacecraft and rendezvous with Starship in low-Earth orbit. This would essentially be a repeat of the Apollo 9 mission, buying down risk and providing a meaningful stepping stone between Artemis missions.

Officially, NASA maintains that the agency will fly a crewed lunar landing, the Artemis III mission, in September 2026. But almost no one in the space community regards that launch date as more than aspirational. Some of my best sources have put the most likely range of dates for such a mission from 2028 to 2032. A modified Artemis III mission, in low-Earth orbit, would therefore bridge a gap between Artemis II and an eventual landing.

Koerner has declined interview requests from Ars to discuss this, but during the Space Studies Board, she acknowledged seeing these reports on modifying Artemis III. She was then asked directly whether there was any validity to them. Here is her response in full:

So here’s what I’ll tell you, if you’ll permit me an analogy. I have in my car a spare tire, right? I don’t have a spare steering wheel. I don’t have spare windshield wipers. I have a spare tire. And why? Why do we carry a spare tire? That someone, at some point, did an assessment and said in order for this vehicle to accomplish its mission, there is a certain likelihood that some things may fail and a certain likelihood that other things may not fail, and it’s probably prudent to have a spare tire. I don’t necessarily need to have a spare steering wheel, right?

We at NASA do a lot of those kinds of assessments. Like, what happens if this isn’t available? What happens if that isn’t available? Do we have backup plans for that? We’re always doing those kinds of backup plans. Do we have backup plans? It’s imperative for me to look at what happens if an Orion spacecraft is not ready to do a mission. What happens if I don’t have an SLS ready to do a mission? What happens if I don’t have a Human Landing System available to execute a mission? What happens if I don’t have Gateway that I was planning on to do a mission?

So we look at backup plans all the time. There are lots of different opportunities for that. We have not made any changes to the current plan as I outlined it here today and talked about that. But we have lots of people who are looking at lots of different backup plans so that we are doing due diligence and making sure that we have the spare tire if we need the spare tire. It’s the reason we have, for example, two systems now that we’re developing for the Human Landing System, the one for SpaceX and the other one from Blue Origin. It’s the reason we have two providers that are building spacesuit hardware. Collins as well as Axiom, right? So we always are doing that kind of thing.

That is a long way of saying that if SpaceX’s Starship is not ready in 2026, NASA is actively considering alternative plans. (The most likely of these would be an Orion-Starship docking in low-Earth orbit.) NASA has not made any final plans and is waiting to see how Artemis II progresses and what happens with Starship and spacesuit development.

What SpaceX needs to demonstrate

During her remarks, Koerner was also asked what SpaceX’s next major milestone is and when it would need to be completed for NASA to remain on track for a lunar landing in 2026. “Their next big milestone test, from a contract perspective, is the cryogenic transfer test,” she said. “That is going to be early next year.”

NASA

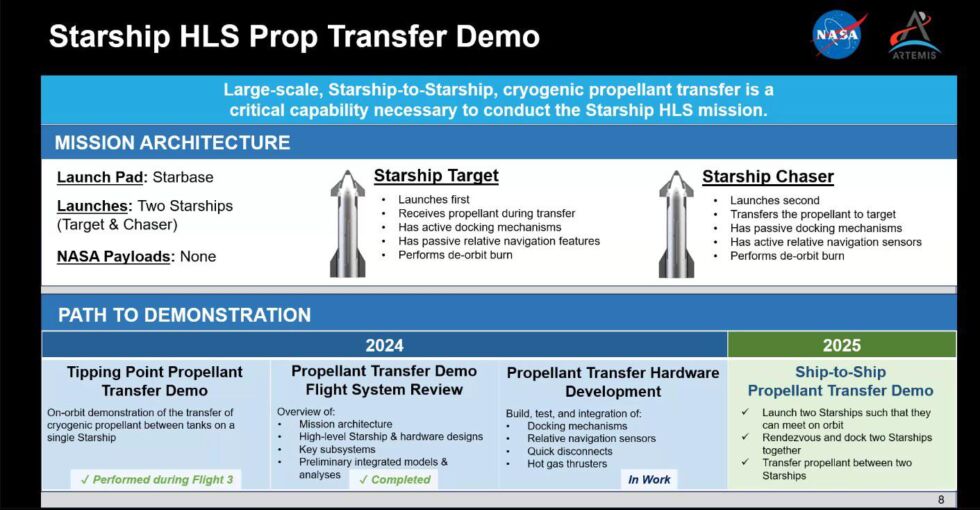

This timeline is consistent with what NASA’s Human Landing System program manager, Lisa Watson-Morgan recently told Ars. It provides a useful benchmark to evaluate Starship’s progress in NASA’s eyes. The “prop transfer demo” is a fairly complex mission that involves the launch of a “Starship target” from the Starbase facility in South Texas. Then a second vehicle, the “Starship chaser,” will launch and meet the target in orbit and rendezvous. The chaser will then transfer a quantity of propellant to the target spaceship.

The test will entail a lot of technology, including docking mechanisms, navigation sensors, quick disconnects, and more. If SpaceX completes this test during the first quarter of 2025, NASA will at least theoretically have a path forward to a crewed lunar landing in 2026.

+ There are no comments

Add yours