Today, the US Environmental Protection Agency announced a suite of rules that target pollution from fossil fuel power plants. In addition to limits on carbon emissions and a tightening of existing regulations on mercury releases, additional rules target coal ash waste left over from power generation and contaminants in the water used during the operation of power plants. While some of these regulations will affect the operation of plants powered by natural gas, most directly target the use of coal and will likely be the final nail in the coffin for the already dying industry.

The decision to release all four rules at the same time goes beyond simply getting the pain over with at once. Rules governing carbon emissions are expected to influence the emissions of other pollutants like mercury, and vice versa. As a result, the EPA expects that creating a single plan for compliance with all the rules will be more cost-effective.

Targeting carbon

The regulations that target carbon dioxide emissions have been in the works for roughly a year. The rules came in response to a Supreme Court decision in West Virginia v. EPA, which ruled that Clean Air Act regulations had to target individual power plants rather than giving states flexibility regarding how to meet broader standards. As a result, the new rules target carbon dioxide the only way they can: Plants can either switch to burning non-fossil fuels such as green hydrogen, or they can capture their carbon emissions.

The EPA did recognize, however, that the decline of coal was handling some of the issue on its own. No new plants have been built in years, and most of the existing ones are growing increasingly old and expensive compared to cheap natural gas and renewables, leading to widespread closures. So the EPA set up tiers of rules based on how long plants were expected to be operating. If a coal plant would be shut within a decade or two anyway, it could simply continue operating as it had or meet less stringent requirements.

In the final rule, this has been simplified down into three categories. Any plant that will cease operations before 2032 will get an exemption. Those that will shut prior to 2039 will have to meet less stringent requirements, equivalent to replacing 40 percent of their fuel with natural gas. Anything operating past 2039 will have to eliminate 90 percent of its carbon emissions.

Natural gas plants will face similar tiers of stringency, but this time based on how often they’re in use. Plants that operate at less than 20 percent of their capacity, such as those that simply fill in during periods of low renewable energy production, can meet regulations simply by adopting low-emissions fuel. Those that run between 20 and 40 percent of the time have to meet operational efficiency standards, while anything that’s operational over 40 percent of the time will have to eliminate 90 percent of its emissions.

Additional changes will allow plants some temporary exemptions from regulations if they’re deemed critical to maintaining grid stability.

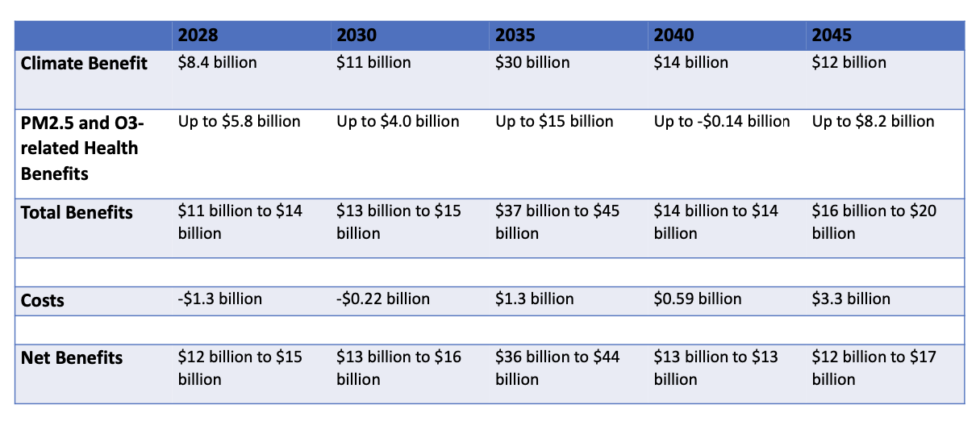

Should the rules survive court challenges, it’s unlikely that more than a handful of coal plants will continue operations. Since burning coal produces a large range of pollutants, this will provide substantial non-climate benefits. The EPA estimates that in two decades, there will be significant declines in nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide pollution, fewer particulates, and less mercury released to the environment. Over the intervening years, this will avoid 1,200 premature deaths, nearly 360,000 asthma problems, and avoid roughly 50,000 lost work days. All of that leads to substantial economic benefits, as seen in this chart.

Thanks to tax incentives for carbon capture contained in the Inflation Reduction Act and the continuing fall in the price of renewables, the EPA estimates that meeting the standards will result in a “negligible impact on electricity prices.”

+ There are no comments

Add yours